For your reading pleasure, I have reread Green Lantern #54.

Yes, there's analysis...Why?

Because we've had activity. A flurry of fine, furious, offensive and friendly activity in the little back alley where feminism and comics meet. You know the place. It's right behind the appliance store where they load the hearses and trucks and.. hearses with their cargo.

I shouldn't joke about this. It's far too serious, even in regards to fictional characters. After all, every character is somebody's favorite (a fact I've recently learned is true), and these stories are meant to be tragic. They're meant to be shocking. And the death and character should be treated with respect. It shouldn't be a joke.

It's inappropriate.

Ahhh, but Dark Humor is part of the impact of the "Women in Refrigerators" list. It's the reason for the title. Otherwise they call it something like "A list of female comic book characters and the tragedies that have crossed their lives." This is not nearly so catchy, nor so funny.

It's the reason the title caught on. The shock of a young man opening a fridge to find his girlfriend. Tickles the unwholesome funny bone of the horror fan in each of us. It allows for an easy joke. When calling for the death of an unliked character ("There's room in the fridge for this one!"), when complaining about a resurrection ("Couldn't they have have kept the fridge door shut?") and when railing against mistreatment of your favorite characters ("Here's another one for the fridge!") or the treatment of female characters in general ("Soon they'll need to rent an appliance store").

Humor is so often used to temper feminist anger, to draw us out of our ranting and bring the conversation to lighter topics. When this is resisted, the "humorless feminist" comments start. There's something grand and fun and uplifting about joking in anger, about making light of a heavy topic even as you seek to impart the seriousness of it. The sarcastic mocking of injustice through your tears and rage that marks the best feminist blogs and websites is captured in the WiR site's title. It enables any of us to go off on a rant with cursory (and sometimes sarcastically worded) link to the list and any of our readers can understand. And it's a free joke. There's no denying the title is funny, in that dark perverted way that a long-time comics reader loves (How else do you think Garth Ennis got so damned popular?), and it's a short well-worded title.

So, is that the secret impact of the Fridge list? The title's funny? Is that all we need to be to replicate the effect of this list?

Well, there's a bit more to it than that.

In fact, I'm going to go so far as to say that although activism, networking, opinion writing, trenchwork, and gathering data to support your argument are all valuable and effective, nothing we do will ever approach the effect of the Women in Refrigerators list.

I'm not downing the recent measures at all. I'm not going away and neither should anyone else. Hell, the very list I'm discussing that inspired these efforts and discussion is completely worthless in itself without the discussion and activity that sprung from it so many years ago.

Nevertheless, just as it's unrealistic to expect voting female candidates into office to have the same monumental impact as gaining the right to vote, it's unrealistic to expect our support efforts to have the same effect as the initial list. The obvious reason being, it was the first. They may have been earlier efforts, but this was the first to catch on. This drew the attention.

The setup helped. It's so innocuous. Just a list. Mailed innocently to a number of professionals and posted on boards. There was nothing angry about it in itself. But when you looked at it and realized the scope of it. The quantity of it. And then you found you couldn't think of a female character who wasn't on the list for something, and if you did it was because she should have been there!

I still see it linked from time to time around the net.

It's crept into our language, even outside the fan community you hear people mention it. For that I credit the name. "Women in Refrigerators." It's strange to hear Ron Marz's writing skills criticized for that scene, it had such an impact. (Though I suspect a lot of the hatred directed at him for that act still revolves around that writer's previous storyline, wherein a beloved male hero was driven completely and utterly insane. And if you'd like to criticize his writing skills, that's a considerably weaker work) A commenter on one of my rants (and I had to force back the crotchety old fan in my response) attributed the emphasis on Green Lantern #54 to the existence of the Internet.

No, I believe it goes a bit deeper than that.

All that said, I can tell you Alex was a character destined to die from the moment she was first introduced in GL #48. I created her with the intention of having her be murdered at the hands of Major Force. I took a lot of care in building her as a character, because I wanted her to be liked and her death to mean something to the readers. I wanted readers to be horrified at the crime, and to empathize with Kyle's loss. Her death was meant to bring brutal realization to Kyle that being GL wasn't fun and games. It was also meant to sever his links with his old life, paving the way for his move to New York. And ultimately I wanted her death to be memorable and illustrate just how truly heinous Major Force was. Thus the fridge. From the reactions, I think I succeeded fairly well at those goals. It's five years later and people are still talking about it. More than anything as a writer, you want the audience to react emotionally to your work, to care.Before I get into it, I'd like to point out that the above defense does nothing to hurt our case. It doesn't matter that her death was intended from the beginning, or that it could have easily been done to a male character. The intention simply doesn't matter, it's the end result. The end result is what supports or overthrows the stereotypes and the symbols involved in the scene. The stereotypes and the symbols that go back centuries. The stereotypes and the symbols still subtly enforced by all aspects of our culture to this day. The stereotypes and symbols we've been trying to overthrow for decades.

-- Ron Marz

Here's where I get the "thought police" accusations. The "You're trying to censor us!" accusations.

No, I want you to think about what you read and write. I want you to be aware of the message you send. I want you to write and draw and create aware of what you are creating. I want you to be able to receive the message, recognize it for the bullshit it is and toss it out. I want you think twice about the overplayed hack attempts at shock writing -- unless you have a damned good story structure around it, because trust me it's nothing new. That's what the Fridge-list proves, that these storylines are not original in any manner. That's the point of this exercise.

In actuality, censorship does more harm than good. Allow me to share the writer's anecdote about this very scene.

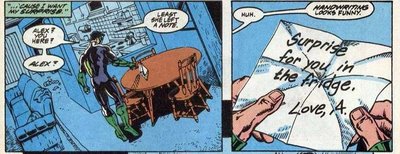

The more infamous example, I suspect, is Alex, Kyle Rayner's then girlfriend. I see a reference to her being "cut up and stuck in a refrigerator." Firstly, you assume incorrectly Alex was "cut up," which is frankly a rather common mistake. The real story behind that page is that as initially written and drawn, Kyle finds her body stuffed into the fridge. Her WHOLE body, in one piece. In fact, I still have a copy of that original page. The Comics Code went bananas and made us change the artwork so that the door was mostly shut. This had the effect of forcing readers to use their imaginations as to what the "unseen scene" was, and a lot of readers went for the most grisly thing imaginable -- a dismembered body. I think this actually says a great deal more about some readers' minds than it does about our original intentions. Score one for the Comics Code.Left to our own devices, we fill in the default automatically. It will, more often than not, conform to societal norms, stereotypes and symbols that have been drilled into our heads from an early age. A fridge door with an obscured body. Of course it's cut up, that must be why they censored it.

I was comparing Alex's death to another female character's. The other was off-panel, with gendered innuendo and interesting positioning. In fact, as she was killed off-panel, it looked suspiciously like a rape scene would be drawn. Kalinara believes it was done on purpose, so that that character would be remembered for the fight she gave before her death. Alex's death was entirely on-panel, she reasoned, because Alex was to be remembered for her death. I added that it had the added benefit of ensuring no one would read rape into the scene.

Compare Mike Grell's disgust at having to clarify that Black Canary was never raped. But the torture occured off-panel and resulted in infertility. What were we supposed to think? Humans always fill in the worst, supported by the mystery. Nothing's hidden unless it's way too bad to see. We fill in the obvious, the worst, the most unoriginal idea. An original idea would have been shown, this will be stock footage. This in turn, through exclusion, supports the stereotyped message as well as if it'd been printed it on the page.

I'd also love to see the script for this page. I'm morbidly amused by the thought of the artist trying to work out how to fit a corpse into a refrigerator.

Anyway...

On one level, it achieved precisely what the writer had intended. Plotwise, it worked perfectly. The intent was a Spider-man style origin, where the hero is off elsewhere while the loved one dies. Rather than have a random villain as the culprit, the writer also created a completely despicable evil -- he threw some interesting parts on behalf of the villain (the flowers he gave Alex with the death threat note, the note to Kyle that implied she'd cooked food for him, the comment about what a beautiful girl she was). The character herself was respectfully treated, an unpowered support cast-member allowed to put up quite a fight against a powered villain. The convention of placing the body in the refrigerator was pure logic. Where else would be put it while he waited an indefinite length of time for Kyle to return?

It was done to shock the readers. There is no denying that. Alex was introduced as the conventional superhero girlfriend, and it was assumed Kyle's origin was done in one, but it had barely begun. His origin story wasn't complete until she was killed. But we, as the readers, were blissfully unaware of this. We allowed ourselves to get wrapped up in the story, and attached to the character and then BAM! She's gone. More Martha Wayne than Lois Lane.

It worked a little too well.

It certainly got everyone's attention.

It made a catchy and humorous title. "Women in Refrigerators."

From the point of view of any fan, it's a cold, dark place to end up.

I very much doubt he realized the feminist symbolism of this. A woman answers the door and dies in the kitchen. The kitchen, such a potent symbol for women. Traditionally, it's the place of a woman, the center of her life, where her proper work is done. It's a vital room, where the health and life of the family is tended to. Where everyone is nourished. Nuturing, the traditional realm of feminity. Alex ventured away from there to answer the door, and was chased back. The villain puts her in her proper place. Teaches her what happens to those who wander too far outside gender norms. He squeezes the life lout of her (intriguing that she's strangled and crushed to death under the restrictive gender roles being symbolically enforced in this scene).

Then, her lifeless body is laid to rest in the refrigerator. The refrigerator, being the central fixture of the kitchen and the family life. The necessities of life are stored inside. The door is used for messages, communication between the members of the family. Communication, necessary to hold the family together. The Mother's traditional job, nourishing the family and fostering the love and understanding that keeps the family bonded. Alex was chased back into the kitchen by the villain. She was crushed to death and shoved into the fridge, even though she was an ill fit.

It gets deeper. A love interest shoved into a food storage unit. You don't put people in refrigerators, you put food there. Women as a consumable item. Here's what I missed from that alternate timeline women's studies class. I don't know where the theory originated, but I've seen it across the net on feminist websites as they critique the culture. The idea that women are there for the use of men, for the consumption of men. That sexuality is something they possess that men must seek and devour.

Objectification, more so than any show of breasts or chests could ever get across. Alex DeWitt was a vibrant personality, she seemed to have a bright future ahead of her. The character's memory is reduced to a body, inside a refrigerator. Woman as an object. Food, sex. A consumable object. All that matter's in the story is the male character's reaction.

Yes, I know that's not what he meant, but that's still what it says.

It made her a more powerful symbol than the other throwaway supporting cast members that writers have brought in to be taken out. It's why she's on the list and Martha Wayne isn't.

It's why she's the mascot for mistreated comic book characters.

Well, that and it's catchy. And gruesomely humorous.

Bon Appetit!

First thought was that you really nailed this.

ReplyDeleteSecond thought was where did Major Damage put all the stuff he took out of the refrigerator to make room for Alex? It's clearly not in the kitchen.

He probably ate it. This is Major Force we're talking about; he's a big guy. He probably also ate the containers and extra shelves.

ReplyDeleteHave you seen the latest issue of "Walking Dead"? One of the women characters is captured, chained arms and legs, legs spread, about to be raped by her captor (who promises to rape her for days unending). Now add onto that the woman is African-American and we have the epitome of sexual and racial oppression (or utter cluelessness).

ReplyDelete"Yes, I know that's not what he meant, but that's still what it says."

ReplyDeleteNo, that's what you heard - there's a difference. All communication is a two-part process: encoding and decoding. The speaker encodes his or her intended message, the listener decodes that message after receiving it. Ideally, the message the speaker intended to encode and the message the listener decoded are identical; in the real world, they rarely are.

Communications never occur in a vacuum: we all bring our own cultural norms, biases, life experiences, etc. to the table, which color the process. Miscommunications - in the sense that the listener decodes a different message than what the speaker intended - abound.

Or to put it more simply: the speaker implies, the listener infers; you're inferring meanings which the speaker (probably) didn't intend. Hardly invalidates your opinion, of course; just means one needs to bring nuance to one's opinion, IMHO.

Marionette and Matthew -- I think that's where the cut up idea came from. My first thought on reading Marz's comment about the censorship was about the shelves in the fridge and where they went.

ReplyDeleteAnon -- Ack!

Ferrous -- Suppose I amended it to "says to feminists"?

I must have mis-stated myself, I was attempting to make room for the nuances without invalidating the reader's natural inferences. I wanted to show what was so captivating about the refrigerator scene, and why the writer's intent does not change what the scene represents.

My point there was two things -- 1) This scene spoke to readers for a reason and I outlined it above, and 2) that despite the author's intent, the story is still valid for analysis because it can be added to a list of like examples to show a social trend.

I'm not trying to say that it occurs in a vacuum at all. In fact, I'm arguing the opposite, that because it does not occur in a vacuum and is surrounded by similar occurances, and happens to be the absolute perfect symbolic example of the complaint means its open season on the work despite all of the author's explanations to the contrary.

I'm also trying to do it without accusing the author of misogyny on a personal level, because just because he used a dramatic convention that is sickeningly indicative of a particular trend doesn't mean everything he writes is trash. I don't think a writer should be condemned unless their whole body of work shows a pattern towards the particular trend (I think I've ranted enough on this site about two particular writers who fall under that category), but I do think a single body of work is open to the criticism because of misogynystic overtones -- especially when it's loaded with symbolism as this one is.

S'funny, I never thought she was cut up.

ReplyDeleteI've never gotten a misogyinistic vibe off Marz, unlike Waid, Meltzer, Willingham, O'Neil, et. al. That would take imagination and passion, neither of which Marz has ever had.

I just reread #54 along with the issues that lead up to it, which I hadn't done before. It's hard to say, knowing what happens, whether Alex comes across as doomed from the moment she appears, but there is something eerily perfect about the way the relationship is written. There is no possible direction for it to go in except down.

ReplyDeleteDan -- Once again, I refuse to apologize for liking Ron Marz so you can take all the cheap shots you want. You won't shame me into dropping his stuff.

ReplyDeleteAnd I have to admit, I thought she was cut up. It's the missing trays. How did he fit her in there with the trays?

And so, apparently, did some of ther other DC writers, because Hal mentions it in a book this week and says he heard Alex was cut up. (Not that Kyle would've gone into that much detail...)

Mari -- Good point. It did work a little too smoothly, especially for a guy based on Peter Parker.

Ragnell: Maybe Alex was a contortionist before she met Kyle?

ReplyDeleteDan -- Ouch.

ReplyDeleteMy university, during Freshman Orientation, requires all incoming students to see a production entitled "In Our Own Words," in which issues that commonly affect women (stalking, "domestic" violence, sexual abuse/harassment, rape) are addressed. One of the most shocking things about the show--to the men, at least--is the portion where people with a green dot on their arm rest (every third one) are instructed to stand up. The lead presenter informs the audience that, in a representative sample of women, those are the percentages of women who will be raped.

ReplyDeleteOne in three.

And yeah, with the missing shelves, it becomes gruesomely logical to assume that Alex was cut up.

Ah

ReplyDeleteI'd like to thank you for this really interesting analysis... and well, the though provocation. It brings far more into life the issues I've started researching the past year because, well, I got tired of the stereotype. It makes me realize how much more serious and still alive this is, even though I'm living it as a 16 year old high school girl.

What strikes me most is how easy it is for the whole thing to runaway from the original intent, and how influenced by culture we are.

Its a sobering experience. Even if I didn't actually read the particular comics, or the series leading up to it.

But hey, this is really influencing- it reached a teenager miles away after she moved to south america. If that doesn't say how influencing and far spreading this is, I don't really know what does.